Photo by : Tom Robertson Photography

This post will discuss some of the key components of the rehabilitation process that should occur in the case of a bone stress injury (BSI) diagnosis. Setting expectations for the rehab process may help the runner commit to the plan of care and advocate for him/herself within the treatment team in order to promote optimal outcomes. Refer back to Part 1 for more information regarding basic pathophysiology, risk factors, and diagnosis of BSIs.

Outline

Initial Plan and early rehab

Establish unloading parameters

Address potential underlying contributing factors

Establish initial cross-training guidelines and activity modification

Mid-stage rehab: pain-free Load progression

Load progression as healing occurs

Return to run

When to begin and what to expect

Initial Plan and Early Rehab

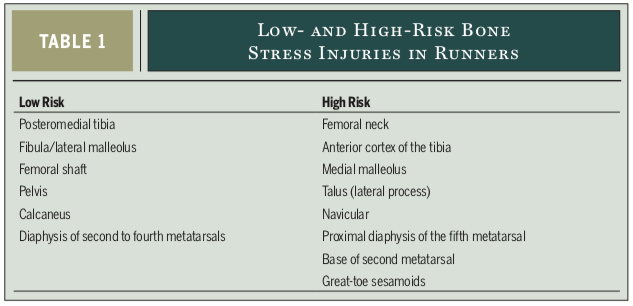

The initial plan of care is focused on setting the athlete’s expectations for approximate time to return to sport, addressing contributing risk factors, establishing weight bearing restrictions if necessary, and outlining guidance on activity modification. Combining knowledge regarding the anatomical location and imaging grade of BSIs provides a framework to formulate the management strategy and potential time to return to running. Recall the discussion in part one regarding high-risk vs. low-risk sites as well as the BSI grading system:

Warden et al. 2014

Fredricson BSI grading classification:

Grade 1: Periosteal edema only. Return to sport: 11.4 weeks (+/- 4.5 weeks)

Grade 2: Bone marrow edema (visible only on T2 weighted sequences). Return to sport: 13.5 weeks (+/- 2.1 weeks)

Grade 3: Bone marrow edema (visible on T1 and T2 weighted sequences). Return to sport: 18.8 weeks (+/- 2.9 weeks)

Grade 4: (4a) Multiple discrete areas of intracortical signal changes; (4b) Linear areas of intracortical signal change correlating with a frank stress fracture. Return to sport: 31.7 weeks (+/- 3.7 weeks)

establish Unloading parameters

Low-risk BSI: Unloading guidelines are guided by pain rules. The presence of pain either during or after activity indicates that the pathological bone is being excessively loaded. The goal throughout rehab is for the athlete to remain pain-free. Walking should be limited to performing activities of daily living. If a normal gait pattern cannot be used or symptoms are produced either during or after walking, partial weight bearing using crutches or a walking boot may be indicated until walking becomes pain-free.

High-risk BSIs are also managed with load modification that promotes pain-free movement. However, due to the risk of delayed healing, and risk for progression to complete fracture, the athlete is more likely to undergo a longer period of non-weight bearing compared to low-risk sites. The table below is an example outlined by Warden et al. (2014) based on their clinical experience.

Identification and Initial Management of Potential Risk Factors

As discussed in Part 1, bone health is very complex, and the occurrence of bone injury may indicate an issue with training load management, energy availability, diet, hormone health, bone health, and sleep habits. The initial period following BSI diagnosis is a good time to evaluate and address potential contributing factors, as it is a time when the runner may be most receptive to behavioral change.

Training Load Management: When the runner returns to training, it may be helpful for them to identify the potential spike in training load, change in running shoes or terrain or lack of recovery that may have lead to his/her injury in the first place. Sometimes the culprit may be obvious, for example a high school cross country runner who increases average weekly mileage from 35 miles/week to 70 miles/week as she initiates training at the collegiate level. A less obvious example would be a case where running mileage was not significantly increased but addition of non-running activity (i.e. skiing) was introduced, or an increase in elevation gain/loss or intensity occurred leading to a large increase in cumulative bone loading. Or, a close look at the runner’s training habits may reveal insufficient rest and recovery to be a contributing factor. By combining knowledge of recent running progressions, changes in training, recovery habits, and life-long physical activity participation, it may be possible to provide a runner returning from a BSI advice regarding future running program design (1).

Screening for Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) and Female Athlete Triad (or male equivalent): As discussed in part one, the combination of low energy availability, decreased sex hormones (amenorrhea), and low bone mineral density is quite common in runners and places an individual at higher risk for BSI. This combination is called the female athlete triad (Triad), and has more recently become known as Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) due to the inclusivity of males and acknowledgement of the many other physiological and performance based consequences that result. The existence of any of the Triad components should prompt more thorough investigation for the others. Screening and early intervention in adolescent females (and males–see below) for components of the Triad are especially important when you consider that 90% of peak bone mass is attained by 18 years of age. Adolescence is a crucial time for optimizing bone health (3). Keep in mind that consultation for a BSI may be the first time that a runner’s issues associated with RED-S are identified. Questions regarding menstrual regularity, onset of menarche, history of eating disorder, purposeful or accidental low energy availability, and previous stress fracture history should be included. Identification of any issues of concern warrants appropriate referral. The 2014 Female Athlete Triad Coalition Consensus Statement recommends the following risk assessment to be administered in cases where presence of the Triad is suspected (1,3):

Female Athlete Triad: cumulative Risk Assessment

De Souza et al. 2014

Female cross-country runners who fall into moderate-risk category have been shown to be twice as likely as those in the low-risk category to sustain a BSI, and high-risk athletes were nearly 4 times as likely (4).

The risk assessment tool has been modified (see image below) to be applicable to males. Research has shown that each one point increase in cumulative risk score was associated with a 27% increase in prospective BSI risk (5).

modified cumulative risk assessment tool

Kraus et al. 2019

Here is a link to a lecture by Dr. Kathryn Ackerman on the Triad and RED-S that provides a great summary of the current literature on the subject. It specifically addresses bone health beginning at 3:45. Refer back to part 1 for links to even more resources.

Bone density: BSIs can occur in relatively healthy bones with normal density. So when should the runner consider a bone density scan to assure that underlying bone health is not contributing to the injury? Bone mineral density scan is recommended when one or more of the “high risk” categories are present or two or more of the “moderate risk” categories are present in the Triad Risk Assessment tool (1,3).

Diet: A dietary screen should be taken, with particular attention paid to possible issues with calcium/vitamin D deficiency, disordered eating, eating disorder, or insufficient food intake. If are suspected to be a contributing factor, the runner should be referred to a qualified sports dietician and potentially a psychologist or therapist to improve ability to properly nourish him/herself for sport. Multiple questionnaires exist for screening for eating disorders and low energy availability including but not limited to:

Sleep habits: Education on importance of adequate sleep should be provided and emphasized due to its importance for general tissue recovery and bone health.

Establish cross training parameters and activity modification

Specific recommendations on what activities will promote wellness and healing will depend on location, severity, presence of pain, and if energy deficiency is identified to be an underlying cause of initial injury. Cross training is a very important component during rehab of BSIs. Cross training includes activities such as swimming, biking, and water jogging and resistance training without overloading the injured bone. But, the athlete and his/her doctor and PT must realize that cross-training restrictions may be necessary to restore a state of energy balance. A collaborative approach should be taken to design a cross-training plan considering optimal bone healing, restoring and/or maintaining adequate energy availability, maintaining fitness and pain-free load capacity, and protecting psychological health.

Being in a state of injury can lead to negative thoughts, sense of social isolation, and loss of identity. These thoughts and feelings can negatively impact outcomes. Practitioners must be aware of the athlete’s psychological state and consider the psychosocial factors associated with outcomes of sports injury rehabilitation. If it seems as though an athlete is not progressing as expected due to psychological barriers, referral to a sports psychologist may be indicated. Adhering to treatment recommendations is paramount, but can be difficult, especially for an individual who has a tendency to push his/her physical limits (a common trait among runners and athletes in general). When a treatment team can harbor trust, confidence, and decrease fear, the athlete will have a higher likelihood for successful return to sport (7).

Below is a diagram I created to summarize the components to consider when devising a cross-training plan:

Created by: Anya Gue, PT, DPT, OCS

If the athlete is diagnosed with RED-S, the the RED-S Clinical Assessment Tool (RED-S CAT) may be used to determine the level of participation in cross-training that is permitted throughout the rehab process (6).

Mountjoy et al. 2015

Mountjoy et al. 2015

Mid-Stage Rehab: Load Progression

While relative overloading is the primary cause for the development of BSIs, recovery is optimized with a balance of rest from aggravating activities and appropriate loading. Appropriate loading can be defined as loading that does not provoke BSI symptoms either during or after activity. When weight bearing pain has resolved and the treatment team believes bone healing is on-track, rehab will continue to focus on pain-free loading progression including weight bearing strengthening and progressive impact activities. Strength training of calves, quads, hamstrings, and hips is important for preparing the athlete’s muscles, joints, and ligaments for return to run, but specific resistance training of the muscles attached to the pathological bone will help promote bone growth and improve its load capacity. Load progression during this stage will be guided by time (respective tissue healing timeline), and pain rules. If pain occurs either during or after an activity, the level of loading must be regressed until further healing has occurred.

Return to Run

The following criteria must be met in order for an athlete to begin a return to run program. This will be determined by the doctor and physical therapist:

Adequate time has lapsed since onset of symptoms, allowing for bone healing to occur

All current activities are pain-free

Strength of the athlete is determined to be sufficient for initiating running

If RED-S is determined to be a contributing factor, athlete must be demonstrating adherence to treatment plan (see RED-S CAT)

Good impact tolerance: demonstrates good control, confidence, and pain-free execution of single leg hopping

Below is an example of one option for a return to run protocol that allows a slow, pain-free progression:

As the return to running is initiated, the physical therapist may identify particular biomechanics that could be modified to decrease bone loading. This could include gait modification, running shoe or running surface recommendations. These recommendations should be made on a case-by-case basis. Below are a few examples:

Step-rate modification: Increasing step rate by 7.5%-10% through gait retraining protocol has been shown to significantly reduce average and instantaneous vertical loading rate as well as peak hip and knee joint work during running (8).

Change from forefoot strike pattern to rearfoot strike pattern: An individual with a 5th metatarsal BSI may demonstrate a natural gait pattern of forefoot strike which is usually associated with a relatively increased supinated foot position during initial contact. This gait pattern results in increased loading to that 5th metatarsal. This individual may benefit from transitioning to a more rearfoot strike pattern, which is associated with less supinated position at initial contact and decreased loading to the 5th metatarsal.

Summary

Diagnosis of BSIs can be challenging, but accurate and early diagnosis is important for optimal outcomes. Treatment of BSIs involves balancing training load with bone load capacity. Multiple factors can influence prognosis, activity modification guidelines, load progression, and bone load capacity. Rehabilitation progression should be patient-specific with a multiple disciplinary team focused on risk factor modification and pain-free progressive return to sport with least risk for recurrence.

Please feel free to comment or contact me at endurancephysioanya@gmail.com with any questions. Thanks for reading!

References

Warden SJ, Davis IS, Fredericson M. Management and prevention of bone stress injuries in long-distance runners. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014;44(10):749–765.

Nattive A, Kennedy G, Barrack MT, Abdelkerim A, Goolsby MA, Arends JC, Seeger LL. Correlation of MRI Grading of Bone Stress Injuries with Clinical Risk Factors and Return to Play: A 5-year prospective study in collegiate track and field athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2013; 41(8): 1930-1941.

De Souza MJ, Nattiv A, Joy E, et al. 2014 Female Athlete Triad Coalition Consensus Statement on Treatment and Return to Play of the Female Athlete Triad: 1st International Conference held in San Francisco, California, May 2012 and 2nd International Conference held in Indianapolis, Indiana, May 2013. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:289.

Tenforde AS, Carlson JL, Chang A, et al. Association of the Female Athlete Triad Risk Assessment Stratification to the Development of Bone Stress Injuries in Collegiate Athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(2):302–310.

Kraus E, Tenforde AS, Nattiv A, et al. Bone stress injuries in male distance runners: higher modified Female Athlete Triad Cumulative Risk Assessment scores predict increased rates of injury. Br J Sports Med 2019;53:237-242.

Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen J, Burke L, et al. The IOC relative energy deficiency in sport clinical assessment tool (RED-S CAT). Br J Sports Med 2015;49:1354.

Forsdyke D, Smith A, Jones M, et al. Psychosocial factors associated with outcomes of sports injury rehabilitation in competitive athletes: a mixed studies systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:537-544.

Willy, RW, Buchenic L, Rogacki K, Ackerman J, Schmidt A, and Willson JD. In‐field gait retraining and monitoring. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2016;26:197-205.