By: Anya Gue, PT, DPT

Many runners have taken the winter moths to take a little break from running and embrace the snow and, for some, the gym. As the temperatures rise, the snow melts, and the birds start chirping, its hard not to lace up those shoes and hit the trail. Especially if you've maintained some decent fitness over the winter, it can be easy to ramp up those miles rather quickly... a quick jog down the river path, a huff up to the "M,"and what's that I hear..., Jumbo's open? Got to hit that! If you're not careful, you may find that you are increasing your running mileage too quickly. How quickly is too quickly? As you may guess, the answer is very dependent on the person as well as underlying fitness, running intensity, ability to recover, and previous running injury history. When a runner increases running volume and/or intensity too rapidly, it is referred to as "training error." While there are so many articles, blogs, and social media posts outlining various stretches and exercises to perform in order to prevent injury, the topic of training and recovery tactics is often overshadowed and underemphasized. I can't tell you how often I have runners come into the clinic saying, "I was doing so well until..." Running related injuries are often due to a relative overuse (tissue overload) due to the repetitive nature of the activity, so you can see why management of your training loads and learning to listen to your body is an essential skill in injury prevention.

In this post, I will outline and discuss some principles and tactics you may want to consider and practice in order to avoid injury due to training error and follow up with a few examples. In a series of following posts, I will dive a little deeper into some tools you may use to monitor composite training loads, how to manage cross training in the "on" season, and how psychological factors may contribute to training error.

For now, lets dive into some tips to get you started:

1) Record your training It only takes a few minutes to jot down your distance, time, and effort for a particular run or cross training activity. This doesn't have to turn into an obsession of paces and perfect distances/times, but you can think of it as simply gathering data. By tracking your workouts, you can have a way to see if you have any rapid jumps in quantity or intensity. If you develop a seemingly random ache/pain or unwanted fatigue, it helps to be able to look at the training history to find a possible cause. Often, people find that they either significantly underestimate or overestimate how much they are training. Either of these can lead to injury or sub-optimal performance.

2) Follow the concept of the "10% rule". Yes, it feels painfully slow in the beginning, but there have been multiple studies indicating a significant increased injury risk when running mileage is increased by >10% over consecutive weeks. This "rule" does not have to be followed strictly, and should vary a little depending on experience, time taken off from running, etc. I tend to use a 10%-30% rule, allowing for a little higher jumps on occasion when a runner has either maintained a good base, or has not had a reduced volume for a very long time, and/or has been cross-training appropriately. However, to have the lowest risk of injury, you would want to stick to 10%. You can find a link to a summary of an article published in JOSPT that discusses some evidence behind the 10% rule Here. If you participate in activities other than running on a regular basis, you do have to account for the stress of these activities as well. I will talk about how to account for the cumulative stress of all of these activities in the a future blog post.

3) Keep long run distance increase between 0.5-2 miles/week. It makes sense that your body may not respond well to a jump in a long run of 6 miles one week straight to 10 miles the next (if it's been months since you've run that far), even if you still manage to adhere to the "10% rule." When weekly mileage is relatively low (10-30 miles/week), your long run should not increase by more than 1 mile. If you are a veteran runner, or you've managed to get your weekly mileage up to 40-50 miles/week, you may be able to safely increase that long run by 1-2 miles at a time as long as you were able to complete your previous long run without any negative outcomes.

4) Plan your training! For some, this may be a weekly outline of the approximate total weekly mileage and where it's distributed. For others, it may be a 3-6 month periodized training schedule with hopes to peak for goal races. In order to follow the previous suggestion of gradual progressive increase in mileage, you have to plan a little so you don't find yourself nearing end of your week with an already 15% increase in weekly mileage only to be tempted by an invite on a social 10 miler that jacks up that increase into the >30%. Planning your training progression may also help you avoid rapid jumps in training volume that occur out of necessity when you realize you have a big race in 1 month that you had to sign up for 6 months ago (because that's how things tend to be now), and realize that your volume is no where near where it should be in order to be adequately prepared. Making at least a loose outline of where you want to spend your miles can be very helpful in giving you an idea of the reality of what your running week should look like. You don't have to stick to it to the exact 10th of a mile and you can always alter as you go depending on outside life influences, and fatigue levels.

5) Plan your recovery! Even more important than planned training is planned recovery. Even the best training plan is only as effective as the recovery. While high training loads are essential for improving physical and psychological fitness for improved performance, there has been ample evidence suggesting that performance will decline if adequate recovery is not allowed. Recovery does not only include rest from physical activity, it also includes obtaining adequate sleep, and nutrition. Fatigue occurs when training demands are high, and recovery is low. Of course fatigue is to be expected with any training plan, but know that your performance will decline and your injury risk will increase if your recovery is consistently inadequate and your fatigue levels continue to increase over a prolonged period of time.

6) Listen to your body! This can be difficult if you have made a training plan and are determined to stick to it no matter what. Even the best laid plans for training and recovery do not always align with what your body needs when you are in the midst of training. Remember that your ability to recover is highly dependent on many extrinsic factors that can change from day to day. It's impossible to know how you will respond to a given training load. Learning how to listen to your body and respect when it may need an extra rest day or when you might be better off skipping a track workout can be very tricky, but so important! So I say, have a plan, but be ready to deviate from it and modify as you go.

Now, consider this equation:

Fitness - Fatigue = Performance

Usually, the end-goal of training is to increase your performance ability. Lets use this equation in a hypothetical case of a runner who decided to start training for marathon after a winter of mild-moderate activity. Let's look at how his equation may look (relative to his running fitness and performance specifically) throughout his training cycle and where he could go wrong if adequate rest is not observed (rating on 1-10 scale with 1 associated with low, and 10 associated with high):

He has maintained some fitness through the winter with his skiing and gym workouts and begins to run more consistently. He feels a bit slower than he has been, but his legs are fresh:

Fitness (4) - fatigue (2) = Performance (2)

As he continues to progressively increase training loads, his equation shifts:

Fitness (7) - fatigue (4) = Performance (3)

He listens to his body, plans a easier week:

Fitness (7) - fatigue (1) = Performance (6)

*He's getting faster!

But lets say, he decides, "wow, I'm really starting to see some improvements, I'm gonna really train hard, because I might just be able to crush this race!" He chooses not to rest, even though his body is tired:

Fitness (7) - fatigue (6) = Performance (1)

*Even though he has not lost fitness, his performance level drops

He is upset to see a drop in his tempo run pace, and decides he is not training hard enough, so he continues to ramp up the effort:

Fitness (7) - fatigue (8) = Performance (-1)

*Uh-oh. Thing's are not looking good. I don't even know what a negative performance means since these numbers are arbitrary, but it seems like it would be associated with increased injury risk, or perhaps a product of "overtraining"

In this example, you can see how recovery can effect your ability to progress your performance and how psychological factors may inhibit your ability to properly practice rest and recovery

Here are a few more examples that tie together all of the above tips.

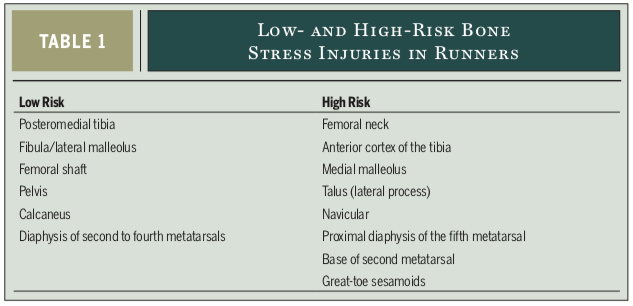

A) Image of an individual's training log who demonstrates several issues in her training progression (this is not a real person, but it is very similar to many that I have seen):